Representación de la población neuronal de la memoria emocional humana

Dustin Fetterhoff, Manuela Costa, Robin Hellerstedt, Rebecca Johannessen, Lukas Imbach, Johannes Sarnthein, Bryan A Strange

The Laboratory for Clinical Neuroscience at the Centre for Biomedical Technology (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid) studies human memory, including how it can be affected by emotion. Through a collaboration with scientists and epileptologists at the Swiss Epilepsy Center in Zurich, Switzerland, they studied brain activity in patients with epilepsy to understand how emotional experiences shape our ability to remember things.

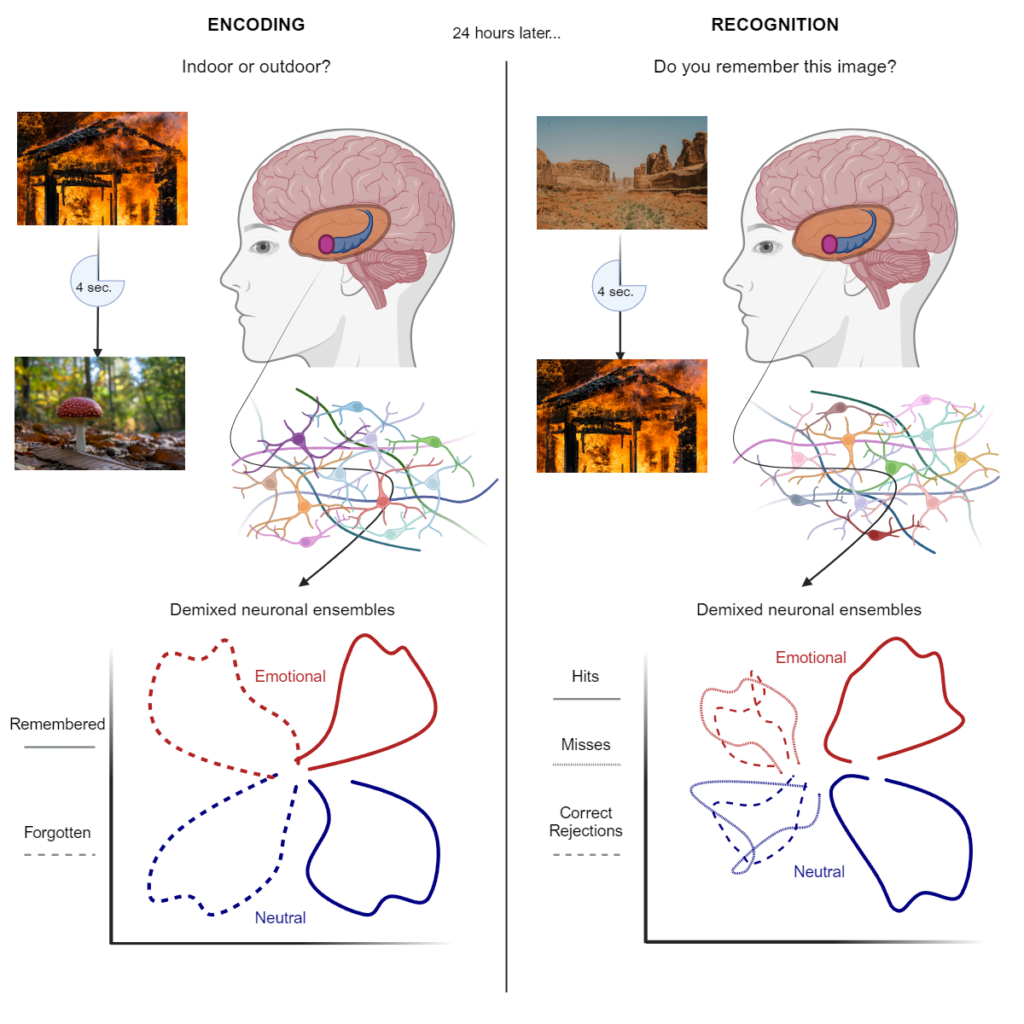

This recent study published in Cell Reports investigates how emotional processing impacts learning and memory by recording neuronal activity from the human medial temporal lobe (MTL), which includes brain regions that process emotion and memory like the hippocampus, amygdala, and entorhinal cortex. They found distinct representations for remembered and forgotten scenes, as well as emotional versus neutral stimuli. Notably, many MTL neurons exhibited “mixed selectivity,” which means they were selectively activated by combinations of different task variables, and illustrated here by responding to either memory, emotion, or their combination.

During memory formation (i.e., memory encoding), neurons exhibited heightened activity for subsequently remembered scenes, particularly emotional ones, suggesting a mechanism for emotional events to enhance memory encoding. They used a technique called demixed principal component analysis (dPCA) to summarize the collective response of the neuronal network to reveal distinct components related to emotion, memory, and their interaction.

When it came to recognizing memories on the next day (i.e., memory recognition), neurons showed differential responses to emotional versus neutral stimuli and remembered compared to forgotten. However, unlike encoding, they did not detect a significant interaction between emotion and memory during recognition. Nevertheless, they did discover that our brains pick up on emotional cues faster than memory cues, which might explain why emotional events stick in our minds. Additionally, they found that misses, old images judged as new, and correct rejections, new items correctly judged as new, were similarly represented in the neuronal ensembles. This suggests that the neuronal populations represent subjective memory experience as opposed to an objective old or new distinction.

Overall, the study highlights the complex interplay between emotion and memory in the human brain. Understanding these processes could help researchers develop new treatments for disorders like PTSD and phobias, where emotional memories play a big role.